Notes on Cloud OLTP

posted on 8 February, 2025 by Dan Vonk in tech, databases

I previously (probably like many “old-skool” C++ devs) thought of cloud computing primarily as renting other peoples’ machines at a high mark-up. However, I’ve been reading up on papers in the databases research field and so thought I would share some of my findings. The use-case I will be talking about here is how modern OLTP databases are designed for the cloud and their corresponding advantages.

OLTP stands for online transaction processing and constrats with OLAP or online analytical processing. The former is a more classical type of database, which is optimised primarily for queries that are short but frequent. For example, modelling payments between bank accounts is a classic OLTP workload. These are simple queries, such as updating a few rows in a table, but should be done quickly and always leave the database in a consistent state, whether they fail or succeed (adhering to ACID standards). On the other hand, OLAP queries are usually far more complex and slower to run, for example, it could query the DB for the year-on-year percentage growth in average sales per customer for each product category in Europe over the last 10 years. Here the consistency properties are less important: eventual consistency is probably acceptable.

Although this e-mail is primarily about OLTP, users of both database types want the same thing. Ideally, they want a database service with high-availability and the ability to scale the service up and down depending on the workload. It should also have high-performance and it should also be cost-effective, which could also include only paying only for what you use.

Traditional OLTP Systems

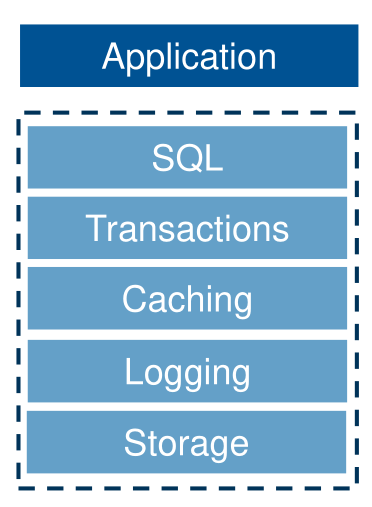

Traditional, monolithic OLTP systems, like MySQL or PostgreSQL have an architecture which has not changed much in the last 30-40 years.

Here, the SQL layer compiles and optimises the query, then sends it to the transaction layer, which provides locking and undo management. It uses data provided by a cache, which gets its data from the logging layer. This layer provides redo logging and crash recovery by maintaining a record of every change made to the database, before they are applied to the storage. When the data is committed to disk, the log is cleared. An example log could be:

| LogStorageNumber | TransactionID | Operation | Table | Row | ID | Before | After |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 000001 | 101 | UPDATE | accounts | 1 | 500 | 400.00 | 500.00 |

Finally, the storage layer handles storing the data in pages (perhaps using a B-Tree) on a durable storage medium such as an SSD+RAID setup.

Positives: - Simple - High performance (low latency) as the data all resides on a single node. - Strong ACID consistency.

Negatives: - Single node of failure. If this node crashes or fails, e.g. due to a power or hardware failure, the service becomes unavailable until it is fixed. By contrast, many cloud DBs as a service gaurantee (DBaaS) a 99.99% (“four-nines”) level of availability in their contracts. That is about max. 5 minutes of downtime per month. - Limited scaling. The only way to handle more queries/second would be to upgrade the CPU or RAM etc. of this node, which has inherent limits.

Scaling Traditional OLTP Systems on the Cloud

Of course, these limitations have been known for a long time and there are various approaches to try to overcome them by turning this monolithic DB model into a distributed system. Distributed systems are commonly assessed based on consistency (as in ACID consistency), availability (incoming requests are always processed) and partition-tolerance (if some of the cluster gets separated from the rest, the overall system still works). Theoretically, a distributed system can only have 2 of these 3 qualities. Scalability is also often assessed, as it’s one of the primary reasons for a distributed system.

Sharding or horizontal partitioning, separates the data into smaller disjoint subsets (shards), where each shard is a self-contained node. Each shard runs its own instance of the database and the application sitting on top will route its query to the appropriate instance.

The verdict is:

- Scalability: Reads and writes are now distributed across multiple instances, improving throughput ✅.

- Availability: One or more shards could still fail, so only part of the database becomes available ❌.

- Consistency: Cross-shard queries need techniques like two-phase commit (2PC) to ensure consistency ⚠️. 2PC ensures either all nodes agree on the write otherwise it gets rolled back. This adds latency and complexity.

Examples of real databases are MySQL with Vitess or MongoDB. Cloud provides several advantages here: - Elasticity: Shards can be created or destroyed depending on workload. - Global Distribution: This is perhaps the biggest benefit. Shards can be strategically spread across multiple data centres, sitting in different regions (availability zones or AZs) to improve query latency. - Pay as you go pricing

Shared Nothing again separates data across independent nodes, each with their own disk and CPU, but here the subsets can overlap, which provides some replication. A shared query layer routes queries to the correct node based on the partitioning key. This can overburden nodes if some parts of the data are accessed more frequently than other parts.

- Scalability: Each node has its own workload, so it’s easy to scale, but users still need to pay attention to load balancing the partitions. ✅

- Availability: If there is enough replication, then a node outage will not affect other nodes ✅.

- Consistency: All of the problems of the sharding approach. ⚠️

A real example is CockroachDB.

Shared Disk databases, as the name suggests, have a shared disk layer at the bottom of the stack. You could do this yourself by using something like PolarFS with MySQL, or use a cloud service like Amazon S3, or even an old-school DB like Oracle RAC. If using S3, one benefits from “infinite” storage with strong consistency (i.e. after every write, the latest value is always read back) as well as an impressive 99.999999999% uptime, as S3 is replicated across multiple data-centres and across multiple regions. Even if one or more AZs fails, such as in the case of a natural disaster, the data will still be readable.

- Scalability: Compute nodes and storage are separate, so each can be scaled independently ✅. Of course this has downsides too: fetching data to/from S3 can quickly become expensive and S3’s latency is also quite high.

- Availability: If a compute node fails, a new node can take over without any data loss ✅.

- Consistency: The centralised storage on S3 means that data remain strongly consistent (ACID), just as the single-node traditional DBs ✅. Two phased-commit is still needed in case one of the compute nodes crashes mid-transaction, for example, so this adds additional latency.

Mixing and Matching

These techniques are all valid and often used, however the latest and greatest cloud-native OLTP DBs take inspiration from all of these models and mix them together. The primary reason is that the interaction between compute and storage is inefficient in the monolithic model because databases organise data into pages before they are flushed to disk. A small amount of updates can therefore create a lot of page flushes and this is even worse if there are multiple replicas (“write amplification”). If the disk is connected over the network, this moves the I/O bottleneck to the network, which is typically much slower. DBAs are able to reduce the frequency of the page flushes, but this comes at the cost of slower crash recovery.

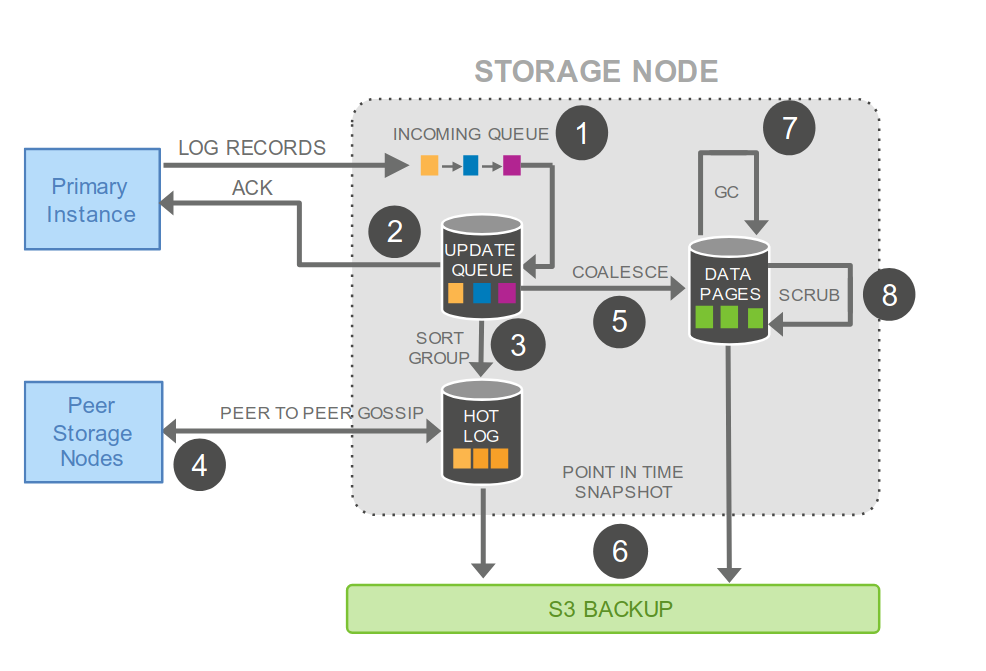

One popular cloud-native database, which addresses this problem, is AWS Aurora, whose key insight was the log is the database. Aurora has both compute nodes and storage nodes. The compute nodes run MySQL database engines but only write log information to the storage layer instead of full database pages when making a transaction. This reduces network I/O as log records are significantly smaller. Furthermore, the storage layer itself is ultimately backed by an S3 filesystem, which is already replicated, so there is no need for replica nodes, unlike in the shared nothing approach.

The storage node handles this log record and goes through the following steps:

- Add it to the in-memory queue.

- Save record to disk and acknowledge.

- Organise the log records and check if there are any gaps in the log.

- Talk with other peers in the storage layer to fill in the gaps.

- Periodically coalese the log records into proper data pages.

- Periodically stage logs and pages into S3.

- Periodically garbage collect old pages.

- Periodically validate CRC codes on pages.

So the storage node does still store pages, but they are used to increase read performance, so that in the case that a compute node needs the data for executing a query, the storage node doesn’t have to re-create it from the log. It also makes recovery much faster for the same reasons.

Another advantage for the compute node is that it does not store any state. It does not manage any locks on tables nor manage any transaction logs. Therefore, it does not need to communicate with other compute nodes when executing transactions, which means there is no need for 2PC (it’s already atomic at the storage layer). Also, if a compute node fails in the middle of a transaction, another node can take over without coordination, because the logs for the transaction are already in storage.

In the paper, Amazon tested both Aurora and a mirrored MySQL setup on an “r3.8xlarge EC2 instances with 32 vCPUs and 244GB of memory”. They find that Aurora has 5x faster write performance than MySQL and up to a 3x faster read performance. It also has better failure recovery because no manual intervention is required if nodes fail. Finally, it has much better scaling than mirrored MySQL because of the separation of the compute and storage layers.

References and Futher Reading

- Verbitski, Alexandre, et al. “Amazon aurora: Design considerations for high throughput cloud-native relational databases.” Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Management of Data. 2017.

- Kleppmann, Martin. “Distributed systems”

- Depoutovitch, Alex, et al. “Taurus database: How to be fast, available, and frugal in the cloud.” Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data. 2020.